Africa Connection | Christina Surowiec | June 10, 2022

In the U.S. and other First World locations, breathless encomiums to magical possibilities now realized thanks to the smartphone have a ring of hyperbole. In Africa, where landline systems were neither extensive nor reliable, life transformations wrought by mobile telephony are far harder to exaggerate. The connectivity revolution south of the Sahara is well underway, but its continued vigorous rollout augurs tremendous further quantitative and qualitative gains for years to come.

About half of adults on the subcontinent have a cell phone, but the number of SIM cards is much higher, close to the nearly one billion sub-Saharan inhabitants. Smartphones (offering handheld Internet access) aren’t quite the norm: some 300 million are in use, but achieving penetration nearly on par with top industrialized economies seems plausible within the medium term. In several countries – notably Kenya, Ghana and South Africa – the cellphone-equipped population share is already at or near 90%, and smartphones are rapidly emerging as the dominant device.

For the next several years 3G and especially 4G extension will support Africa’s smartphone connection growth. Only a couple of pilot projects (in Nigeria and South Africa) are 5G-based, and only 3% of smartphones now in use on the subcontinent are 5G-enabled. At the low end, 2G expansion has stalled out. Demographic momentum will propel mobile subscriptions. In Africa, the youngest continent,

hundreds of millions of people reaching or about to reach young adulthood consider personal

smartphones a necessity, not just an accessory. Cost is a countervailing factor, but not a formidable barrier, as the already high adoption rate shows.

There are two widely promoted models for affordable Internet-enabled telephony:

►“basic” phones, with a limited number of

corporate-curated apps (e.g., Facebook,

Instagram), selling for about $30;

►standard albeit lower-end fully Internet-enabled

smartphones, costing $100 with three-month

installment payment plans widely available.

Reporting suggests that the stripped down Facebook phones are only popular with a niche clientele who are less interested in tech. By contrast, most digital adopters – especially the burgeoning youthful segment – want the whole Web, and want it unmediated.

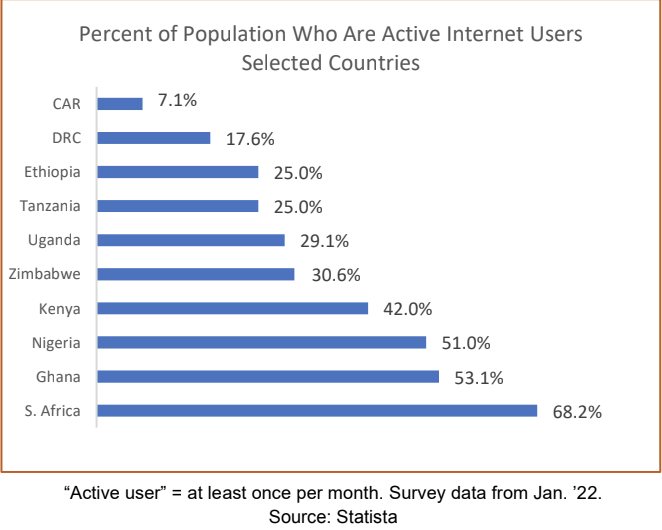

The data shown above are problematic as survey quality might be questionable and circumstances such as the Covid pandemic likely skewed activity. In a place like Kenya, by many accounts nearly brimming with smartphones, the reported Internet use rate seems low. While this is quite a recent development, sub-Saharan Internet access is now principally via smartphone, rather than urban Internet cafes, though these remain popular and serve a vital function for many. Home computers are extremely atypical.

In the previously mentioned survey on Internet use by country, a correlation between low stability/lower development and weak Internet uptake seems robust enough. Will young Africans parlay excitement over soaring digital opportunities into more effective pro- stability, pro-sustainable development politics?

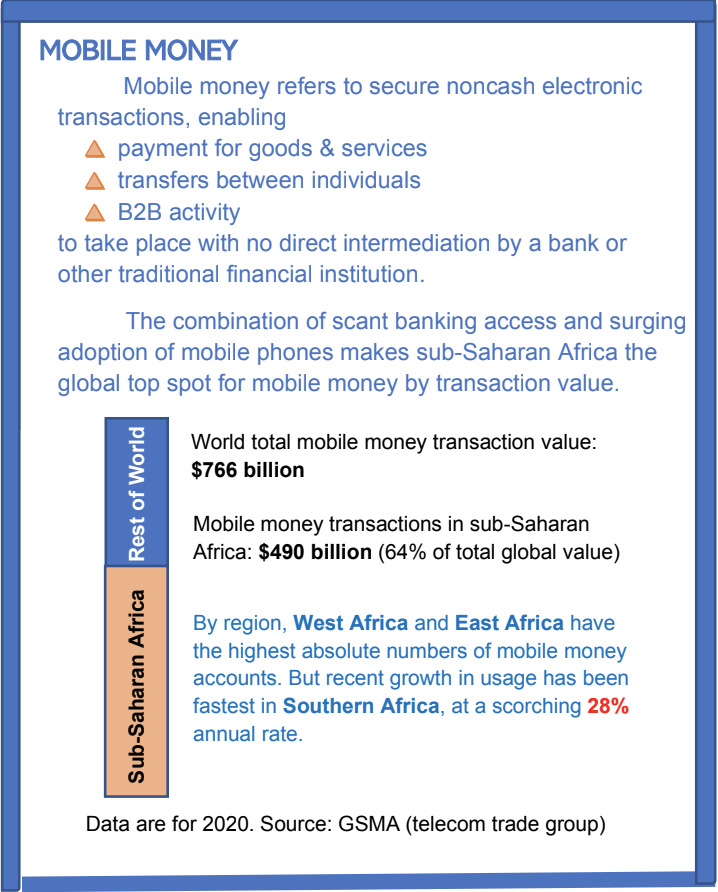

The cell phone revolution has upgraded many Africans’ financial situations. E-money or mobile money apps (not the same as cryptocurrency) pack into a small device the equivalent of a cash wallet plus a bank account. As many transactions occur locally, the multiplier effect from money circulating within communities palpably enhances personal economic leverage and helps to raise living standards. Overseas remittances, crucial for

many families, are also morphing into phone delivery format, although in this category the traditional banking sector using newly developed dedicated software continues to predominate.

Mobile phones are a market transparency tool for smallholder farmers, still a most representative occupation on the continent. Unscrupulous traders now find it increasingly difficult to cheat producers on the price tendered for coffee and cocoa, since growers can instantly look up the current world price.

Phone-based information does not remove the need for regulation and governance, but it certainly makes effective regulation and governance more feasible. The telecom industry accounts for 8% of sub-Saharan Africa’s aggregate GDP, compared to a 5% global average. If anything, this figure understates the sector’s importance. There is almost nothing, aside from taste and smell, that an app (potentially, anyway) cannot help you do. As an example, conservation apps are brightening future prospects for iconic animals. The ability to track herd movements is supporting creation of appropriate wildlife corridors, thereby promoting farmers’ and elephants’ peaceful coexistence. Electronic surveillance makes poachers’ movements easier to track and suppress, too.

Getting there: from subsea cable to the “last mile”

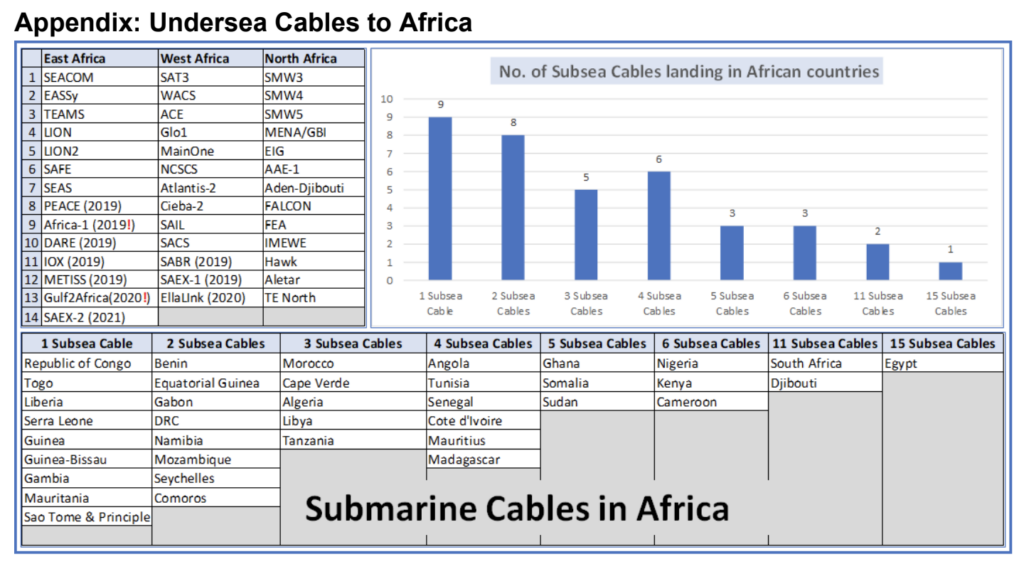

One cannot sugarcoat the fact that substantial financial and regulatory (much more than technical) barriers to a fully online Africa remain. Yet, the continent’s telecom proliferation through the last decade or so has emplaced so much digital infrastructure already, prospects strongly favor enhancing, not stranding, these assets. The first foothold is high-capacity undersea cable links. A threshold was the 2011 launch of a London-Lagos-Cape Town fiber optic utility, kickstarting digital activity in West Africa and southern Africa. The connectivity extravaganza has proceeded apace since then despite some pandemic-related delays. A Hong Kong-financed project that connects Mombasa, Kenya to a high-capacity system joining Europe, Asia and Africa went live this March. In West Africa, a month later, WIOCC (West Indian Oceanic Cable Company) in alliance with Google announced landing of a new high-load cable in Lagos. Today, only three coastal African countries/territories – Equatorial Guinea, Western Sahara, Eritrea – lack high-speed Internet access via oceanic cable. The situation vis-à-vis cable connections to the coast actually shows more bandwidth than demand for it at the moment. That will undoubtedly change, probably quite soon, but divvying up bandwidth resources optimal will require prescience, savvy, and institutional credibility. The WIOCC-Google augmentation stresses its open access formulation, meaning any carrier with a suitable project can apply to use the resource. But how much to use is a complex calculation. For instance, if streaming services become popular, the purveyor will need to lock up enormous capacity to satisfy customers.

Conversely, more compact applications could reach large target groups while consuming minor chunks

of bandwidth. “Last mile” connections are a global, not just African challenge. Sub-Saharan Africa is a

relatively hard case in this regard, however. The subcontinent’s mosaic of countries and telecom carriers, its limited post-colonial governance experience, and the wild card factor of some fragile and/or conflict-affected states, pose a complicated set of issues for any hopeful entrepreneur. All or nearly all telecom providers active in Africa support the concept of open RAN (radio access network) as the best basis for expansion and service provision. This means cell towers are carrier- and vendor-neutral, not proprietary to a single firm’s system. Such a setup not only meets a social equity test; it also facilitates collaboration

among competitors to improve overall access, and should make timely technological upgrades more

practicable. The fly in the ointment stallin deployment, according to the business press, is uncertain governance and thin, changeable regulation. While companies were highly confident they would see a good return on investment from open RAN towers, insecure ownership rights under many regimes made the businesses hesitant to erect them.

Alluring data centers: two recent Nigerian deals

The wealth of bandwidth coming into the continent is piquing investor interest, as two recent acquisitions in Nigeria demonstrate. Last October, the U.S.-based online services firm Digital Realty announced its $29 million purchase of Medallion Data Centres, which operates from locations in Lagos and Abuja. Digital portrays this move as an opening gambit for African expansion projected to include Kenya and Mozambique, as well as Nigeria, with the ultimate investment total possibly going as high as $500 million. An even larger investment, for the time being, is $320 million from the American systems architecture company Equinix to acquire MainOne, one of West Africa’s top e-commerce and data services providers. As a point of comparison, a similar deal that Equinix recently made in Mumbai (GPX) was for approximately half the amount it paid for MainOne. Is this activity a sign that global digitally focused business is starting to shift its center of gravity from India to Africa?

Not so fast, probably. The call center sector in Africa, particularly West Africa, is less developed

than it could or arguably should be. Industry-wide, turmoil over offshoring versus re-shoring clouds the

outlook; recent world events including the pandemic magnify this uncertainty. That stated, West Africa offers a large pool of educated, tech-capable individuals, fluent in English and/or French, and perfect time zone compatibility with Western Europe. Data-related jobs are headed to the region, though the numbers, timing, and exact configuration are difficult to specify.